Road trip for low-carbon asphalt

Low-carbon asphalt materials are being trialled on England’s major roads.

In 2022, England’s National Highways announced it had become the first major roads organisation to achieve a globally recognised accreditation for its commitment and ambition to cut carbon emissions.

Recently re-verified, the PAS 2080 accreditation underpins its efforts to reduce carbon emissions in the design, construction and operation of England’s strategic road network as part of the acceleration towards net-zero. The network comprises more than 4,500 miles of motorways and major A-roads that connect towns and cities.

Steve Elderkin, National Highways’ Director of Environmental Sustainability, explains that the government-owned business has 'stretched targets' to achieve its net-zero ambitions. 2030 is the deadline for its own operations and 2040 for maintenance and construction activities (see box-out below).

England’s National Highways targets for net-zero

- Corporate emissions – net-zero by 2030.

- Maintenance and construction emissions – net-zero by 2040, including a focus on the asphalt, concrete and steel sectors.

- Road-user emissions – net-zero by 2050, includes helping to decarbonise heavy goods vehicles and support the uptake of electric cars and vans.

Driving research

The organisation is steering best practice in construction and maintenance with an emphasis on low-carbon materials (see box-out below).

Elderkin explains that asphalt is used for road surfacing on more than 96% of England’s strategic road network. Most of the material (63%) goes into the surface course while the rest is used for the layers below. Bitumen is a key component of traditional asphalt, acting as a binder.

However, with asphalt contributing 15% of National Highways’ total construction and maintenance emissions, finding lower-carbon alternatives is critical.

Since National Highways published its net-zero roadmap in 2021, it has been funding research into various technologies to reduce carbon emissions. These include:

- Bio-binders (or bio-component bituminous binders) – lignin and tall oils produced from industrial processes are used to reduce how much bitumen is needed and lock the carbon contained in the biomaterial into the asphalt.

- Long-life binders – these typically have been polymer-modified or include bituminous binders that age harden and oxidise at a slower rate to extend the road’s life. Although initially expensive to employ, improving the asphalt’s durability reduces the frequency of resurfacing and replacing the layers on roads. This reduces carbon emissions across a road’s lifetime.

- Recycled plastic additives – used as a substitute for bitumen in asphalt for fewer carbon emissions. Plastic additives also reportedly make asphalt stiffer when used as a binder modifier, reducing rutting. They can also minimise moisture impact on asphalt over time and, like long-life binders, may reduce how often the road layers need resurfacing or replacing.

- Crumb rubber – made from broken-down tyres, it can be mixed with asphalt at higher temperatures and used as a polymer to modify bitumen or replace part of the aggregate, improving the road’s durability and resistance to poor weather conditions. This material may also reduce the frequency of resurfacing and replacing layers.

- Graphene additives – mixed with an asphalt binder at high temperatures, they can make the road more durable, weather-resistant and reduce rutting, again reducing maintence requirements.

- High-percentage reclaimed asphalt – reduces the demand for virgin aggregates and bitumen. Current road standards permit up to 20% of recycled asphalt in a road’s surface and up to 50% reclaimed asphalt in other layers. National Highways can use higher percentages of reclaimed asphalt if the business can demonstrate it delivers carbon and environmental benefits without impacting on long-term performance. As the business plans to use more reclaimed asphalt in the future, it is looking to see how it can update standards for this material.

- Half-warm asphalt – is produced at lower temperatures than traditional hot-mix and warm-mix asphalt. As it takes less energy to produce, National Highways says fewer carbon emissions are emitted. The business can also lay more half-warm-mix asphalt than hot-mix asphalt in the same amount of time, because it does not require as much time to cool down before the road can reopen.

- Bio-rejuvenators – bio-based materials that can be added to reclaimed asphalt to restore its initial properties so that it can be effectively used on the road again – reducing the demand for virgin aggregates and bitumen.

On a journey

National Highways has started to trial these various materials on sections of motorways and major A-roads with partners like Shell, AtkinsRéalis, Heidelberg Materials and Tarmac. The materials are monitored to assess their durability, with the findings being used to update National Highways’ specifications and standards.

By working with Nottingham University, UK’s Transportation Engineering Centre, Elderkin says they can better understand the materials’ performance and ensure they meet specifications.

One trial project achieved the Institution of Civil Engineers’ (ICE) Carbon Champion status last September. The trial – using asphalt with polymer-modified bio-binder on the A30 in Devon – showed that replacing a percentage of the bitumen binder with a bio-based alternative can reduce asphalt’s greenhouse gas emissions by 20% over the lifecycle (raw material extraction, processing and manufacturing).

This was reported as the first time that polymer-modified binders, including a bio-binder, had been laid on a strategic road network in its surface course materials. Two binders containing biogenic material were tested – Nynas’s Nypol RE and Shell’s Bitumen CarbonSink.

The ICE case study describes how 'a control section of surface was also laid using conventional binder, to compare the long-term performance of the trial materials with that of traditional bitumen-based asphalt”. After 18 months, the novel materials reportedly showed similar performance to that of the control section.

Biogenic asphalt has since been laid on two further sections of the road network in combination with other technologies, namely polymer-modified bio-binder with warm-mix asphalt and reclaimed asphalt on the A2 near Canterbury, Kent, and the A34 in Oxfordshire. The aim was to reduce carbon emissions even further and promote recycling.

Meanwhile, proprietary graphene additive in warm and hot-mix asphalt has been laid down on the A12 in Essex.

Hitting the accelerator

A smaller-scale trial that took place last June on part of the M11 in Essex is one-of-seven projects that reached the first stage of National Highways’ Accelerated Low Carbon Innovation programme.

A collaboration with Connected Places Catapult, the programme awarded each recipient between £15,000 and £30,000 to develop trial proposals with National Highways and its tier 1 suppliers. Four have received additional funding of up to £80,000.

In the M11 trial, Seaham-based Low Carbon Materials (LCM) is applying its proprietary ACLA ‘carbon-negative aggregate’ with the support of Skanska and Tarmac. ACLA is billed as a ‘carbon sink’ sequestering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

LCM claims that 3-10% of ACLA is required by weight of the total asphalt mix to achieve net-zero asphalt. 'What was great about the [accelerator] catapult was that it got going quickly. It moved from being a concept in December to a trial on the network in June,' explains Tim Smith, Senior Technical Manager at Tarmac.

As straightforward as this sounds, Smith reveals that finalising sites to trial materials is not easy due to road-user demands, and so the risk of failure must be minimised in the laboratory before site roll-out.

Ahead of the exercise, Tarmac tested the ALCA in its R&D facility to confirm the artificial aggregate achieved standard test requirements for construction of asphalt.

'We did some trial mixes and performance testing to see whether we could produce asphalt by substituting around 5% of the natural aggregate [with ALCA],' shares Smith.

'If you look at how a road is constructed, it’s made of layers of different types of asphalt mix and then a surface course on top, which is important because it must have good skid resistance. You can only use very specific aggregates in the surface course.'

When the pre-trial tests suggested the ACLA couldn’t provide the required skid resistance, Tarmac incorporated the aggregate into the next layer down – the binder course.

For a structural layer material that sits below the surface course, the asphalt specialists were interested in assessing its stiffness to ensure it could provide sufficient support and was resistant to cracking when put under vehicle-wheel strain.

Tarmac also undertook wheel-tracking tests to assess the material’s ability to prevent rutting – a depression in either surface or binder course caused by either secondary compaction or asphalt flow.

During early 2024, the business undertook further extensive tests to assess ACLA’s durability and ensure it complied with National Highways’ specifications.

'Binder course has got an expected life of 40 years, so you’ve got to get it right, because if you don’t, you’ve got some very expensive problems,' explains Smith.

A 40-50m test strip of asphalt binder course containing the ACLA aggregate was eventually laid down on part of the M11 in one night. A control section made with standard binder-course material of similar size was placed in front.

A surface course was laid over both. Smith explains that mixing the 5% ACLA into the binder course presented a challenge because it doesn’t share the same characteristics as conventional aggregate. However, as asphalt has excellent recycling properties, Tarmac was able to pre-blend the ACLA with reclaimed asphalt milled from old roads.

Early results from the ACLA performance testing, repeated post-trial in Tarmac’s R&D facility, have been positive.

Paving the way

A more detailed evaluation is underway on what National Highways describes as 'the lowest-carbon asphalt resurfacing scheme' attempted to date on a section of the A64 in West Yorkshire.

National Highways employs an Asphalt Pavement Embodied Carbon Tool (asPECT) to calculate the material’s carbon footprint and is also developing a carbon accounting tool for measuring improvements.

According to their calculations, the A64 trial should deliver 70% carbon savings (reducing emissions from 321t to 96t) through a combination of lower-carbon materials, equipment and working methods.

'The A64 project not only looked at embodied carbon in the materials themselves, but ensuring the entire process reduces carbon as much as possible, so looking at plant and machinery and whether that can be run on electric or renewable fuel sources, and undertaking the work in a total closure rather than a lane closure overnight,' explains Donna James, Technical Director – Pavements at AtkinsRéalis.

Elderkin says using electric rollers on the October 2024 trial reduced tailpipe emissions. In addition, a hydrotreated vegetable oil ran most of the haulage vehicles and other non-electric equipment.

The surface asphalt materials also include an anti-ageing additive to extend the life of the road surface by three-to-five years.

Beneath the surface

The A64 project builds on research led by AtkinsRéalis on future asphalt surface courses. James’ team should complete Phase 2 in March.

'As part of this phase, we’ve done trials and laboratory testing of bio-binders that have been combined with warm-mix asphalt technology and high-reclaimed asphalt content, so up to 30% reclaimed asphalt in the surface course,' she says. 'We’ve also trialled a graphene-enhanced, asphalt surface course that includes up to 40% reclaimed asphalt and a bio-based rejuvenator with 50% reclaimed asphalt.'

James explains that when high amounts of reclaimed asphalt are used, testing needs to validate that the recycled aggregates can mirror the same properties as virgin aggregate. She notes, 'The reclaimed asphalt that we take off the road includes some old bitumen that can be reused, and bitumen is one of the biggest contributors to asphalt’s carbon footprint.'

National Highways and its partners also trialled an echelon paving method, which involves laying asphalt manufactured with lower-carbon content across the entire A64 trial section, rather than in lanes to minimise surface joints to extend the road surface’s lifespan. Although the trial took place last October, evaluation and testing of the surface-course material is ongoing.

James says there isn’t a single 'magic test' that will mimic how an asphalt material will last over time. Testing will look at properties like stiffness and fatigue performance to assess resistance to cracking and the risk of rutting caused by wheel wear.

Nottingham’s Transportation Engineering Centre is again providing laboratory-scale validation. Dr Nick Thom, Highway Engineering Specialist at Nottingham, explains, 'You get a cylinder of asphalt from the road, you put it up on its side and you compress it across one diameter. You repeatedly compress it and you measure how much it deforms to work out its stiffness.'

To assess wheel-rut risk, the team undertakes both dry and underwater wheel tracking to reflect different weather conditions.

'Underwater, means you allow water to attack [the material] and, if it’s a poor material, the surface aggregate might start coming out. You’d get poor performance in the road from that,' adds Thom.

Another test involves taking a slab of material measuring 30cm in length and 50mm in thickness and tracking a wheel set at 20o backwards and forwards to mimic a heavy goods vehicle. 'If it’s a poor material, it will start to rip up and you’ll lose material from the surface,' Thom says.

The team also investigates reflective cracking, when a crack in the underlying material extends to the asphalt overlay.

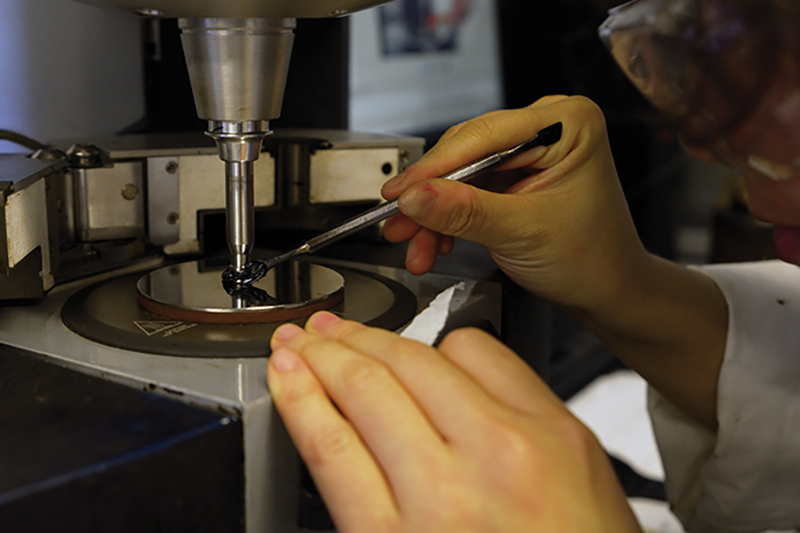

While the bitumen binder recovered from the aggregate is tested using a dynamic shear rheometer to assess its performance.

'We put a little drop of bitumen between a steel cylinder above and steel plate below, so the specimen is like a disk of bitumen, and the test involves rotating the top spindle of steel backwards and forwards,' Thom explains. 'You can rotate it at different frequencies, and it is temperature controlled. You can build up a good picture of how the bitumen behaves. The dynamic shear rheometer gives you data on cracking. You can do repeated spindle movement until a crack develops in the bitumen.'

Should the project be extended into a third phase, James anticipates returning to trial sites to evaluate the materials’ performance further.

'With our future asphalt surface course project, we looked at the end-to-end process right from the start,' she explains.

'As soon as we started to look at the bio-binders, we did a review of the existing standards and specifications to say, ‘Right, what would be the barrier if National Highways wanted to implement these tomorrow? What would need to change legally so they are allowed to do that under construction products regulations?’

'We gave them the big picture, which should lead to the implementation of these technologies into standards and specifications, and business as usual, on a much shorter time scale.'

Well-travelled

According to National Highways’ Annual Report and Accounts 2023-24, published last July, its total emissions were 567,794t of CO2e, an 8% increase on 2022-23.

However, Elderkin explains, this spike is due to increased activity on the strategic road network and improvements in how National Highways collects data. The longer-term picture is that, since 2019-20, carbon emissions associated with maintenance and construction have reduced by 2%.

'The annual report shows we have reduced our [corporate] emissions by 66% since 2019-20, with an 11% year-on-year reduction in the past year,' he adds.

'We now purchase 99.98% of electricity from a zero-carbon source. Our light fleet is 97% electric or hybrid, with 16% fully battery-electric.'

With National Highways re-verified for the PAS 2080 standard, it expects all its large and medium suppliers engaged in construction and maintenance to achieve accreditation by late 2025. National Highways is keen to stay on course.

Materials in focus

National Highways roadmap to net-zero includes a commitment to net-zero emissions from construction and maintenance by 2040. The largest source of emissions in this area is from materials productions. With this in mind, roadmaps for concrete, steel and asphalt have been developed in collaboration with the supply chain and relevant trade bodies.

The roadmaps describe how to reduce emissions by decarbonising raw materials, the manufacture of materials, and transport and construction.

Measures including specifying low-carbon concrete mixes to reducing emissions associated with cement clinker production.

For steel, the priority is “maximising the impact of emerging and available technology to reduce emissions, primarily from steel production”. This involves optimising existing manufacturing routes to reduce waste and improve productivity, as well as moving to alternative fuels.

A similar focus is laid out for asphalt and expanded on in this article.

National Highways acknowledges that 'although we need to achieve a minimum 90% reduction in our overall construction and maintenance emissions by 2040, this is not going to be delivered through a 90% reduction in emissions from material manufacturing. There is also a need to reduce the quantities of materials we are using through building less, getting it right first time and extending the life of our existing assets.

'However, the roadmaps do not forecast changes in material quantity and type at this stage.'

Full circle

Another winner of National Highways’ Accelerated Low Carbon Innovation programme is Circular11, which recycles mixed, low-grade plastic into fencing.

'There is at least 60,000km of road network that has fencing along it to demarcate boundaries between roadways and private landowners, amounting to 100,000t of material,' explains Co-Founder Benjamin Gibbons.

'We’re creating a new process that allows us to use post-consumer municipal waste and hard-to-recycle materials from construction companies. Crucially, this is more environmentally impactful because you can divert something that would have gone to incineration,' he says.

It receives highways-related waste streams from Tier 1 contractors like Kier and Vinci.

Circular11 has adapted its extrusion manufacturing process using machine learning to autonomously optimise the variable plastic compositions into lines, standardising its mechanical properties on the input side.

'If it’s not already granulated, we will granulate it,' explains Gibbons.

'It then goes through a chemical characterisation and that’s where much of the innovation for our manufacturing is. We need to understand the chemical compositions of the waste streams in real time. Although that is challenging, it’s an essential step for us to be able to use difficult-to-recycle waste.'

Next, the chemically treated granules enter a compounding stage, during which they are extruded into a construction-grade composite material using polymer engineering.

Circular11 has deployed its fencing products at Kier’s depots to validate that they can be installed and transported as quickly as timber alternatives.

'What we’re looking at next is shifting it from a trial to a procurement basis, where we can start to integrate the material into traditional procurement chains,' Gibbons continues. He says the business has already deployed its fencing for local authorities like Surrey County Council.

Circular11 has also worked with verifiers of environmental product declarations to certify carbon emissions at each stage of the lifecycle and to reflect influenced emissions, which track the mitigation of upstream and downstream emissions.

Gibbons says, 'Because we use material that would have gone to energy from waste, there’s a net-carbon saving of about 0.5-0.55t of CO₂ per tonne of product that we produce.'