MBT - supporting members for nearly 100 years

Peter Bate, the grandson of a former IMM member, was researching his family history and discovered that the benevolent fund had been a great help to his grandmother in the late 1920s

In January 2018 the MBT was approached via Frances Perry at IOM3 by Peter Bate, the grandson of a former IMM member. Peter was researching his family history and knew that the IOM3 benevolent fund had been a great help to his grandmother in the late 1920s. This is his family’s story.

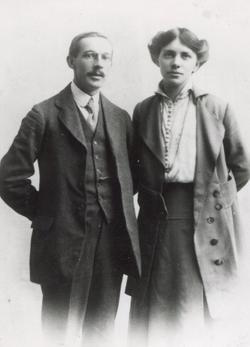

Stephen Conrad Clavell Bate (in the middle of the photo) was a mining engineer and a member of the Institute of Mining & Metallurgy, now IOM3. He was married to Christiana, known as Chrissie, in 1916 when he was 30.

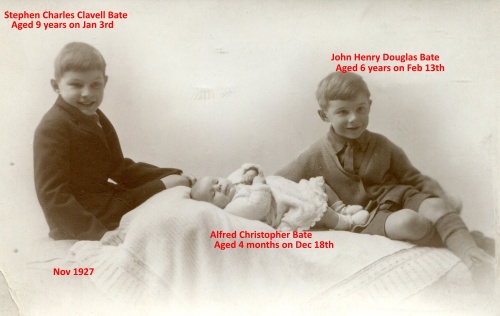

In 1926 he had been unemployed for nine months when he found a job tin mining in Nigeria. He had worked in Nigeria before during WW1 and he left the UK in December 1926. When Stephen died in Jos during April 1928 of a cerebral tumour he had three sons: Clavell (9), John (6) and Kit (1). He had never seen his youngest son. Stephen was buried at St. Piran’s church; fittingly St. Piran is the patron saint of tin miners.

Some years later John wrote:

“My last real family memory, before we left Anerley Hill, was the night my mother received the telegram saying that my father was dead. She knew he was ill, but in those days it was impossible for her to go to Nigeria. This was a double blow because of her sister, Blanche, dying a couple of years earlier. She was with neither of them when they died. When the telegram came she was holding Kit in her arms. Clavell and I were standing by her and she read the telegram aloud and explained to us what had happened. My mother was 35 and had been married for 12 years. My parents’ married life was one of continual movement and separation.”

Before leaving for Nigeria Chrissie had nagged Stephen to take out life insurance. When the death certificate eventually arrived she was able to use the insurance money to lease a house in West Dulwich close to her sons’ school and parents.

Chrissie was now faced with two further problems: finding money to live on and keeping her family together. She was already under pressure to have her sons adopted.

Chrissie applied to the benevolent funds of two of the professional bodies to which her husband belonged: The Institution of Mining & Metallurgy and the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. In those days engineering was a more broadly defined discipline and Stephen had worked as a mining, mechanical and chemical engineer. The IMM Benevolent Fund agreed to give her £5 per month and the IMechE agreed £3 per month. These grants were reviewed and adjusted at regular intervals. Her brother Charles, also an engineer, gave her £10 per month for the rest of her life. She also took in lodgers and when Kit started school taught domestic science in Clapham at a girls’ residential home.

The two eldest boys served in the REME and the Royal Artillery during WW2. When the war ended all the boys were back in the UK, rebuilding their lives were moving out into the world. Chrissie found this natural evolution of her family difficult to adjust to. The strain of being a single parent took its toll and she died shortly after her 60th birthday in 1952. She couldn’t have known that she would have nine grandchildren or that her sons would build successful careers and happy lives. Her primary instruction to her sons was to get a steady job with a pension at the end of it. This they all did with one becoming a senior engineer at the BRE, one a headmaster of a secondary school and the youngest a Major General.

Without Chrissie’s determination and the financial support she received from institution benevolent funds such a positive outcome from the shattered family in 1928 would have been considerably less likely.