Knowing your market - academics turn entrepreneurs

Spin-out companies involve academics entering new territory to commercialise their research. Alex Brinded spoke to three academics-turned-entrepreneurs about their journeys and experiences.

Dr Chiraz Ennaceur (CE) is CEO of CorrosionRADAR,

which provides systems to identify, localise and monitor the presence of corrosion and moisture under any type of insulation or asset. Having finished a PhD in France and then a postdoc in the Netherlands, Ennaceur realised that academia was not for her, and moved to the UK to work at the Welding Institute for 10 years. She met the inventor of the corrosion detection system and his team at Cranfield University through this work and started CorrosionRADAR six years ago.

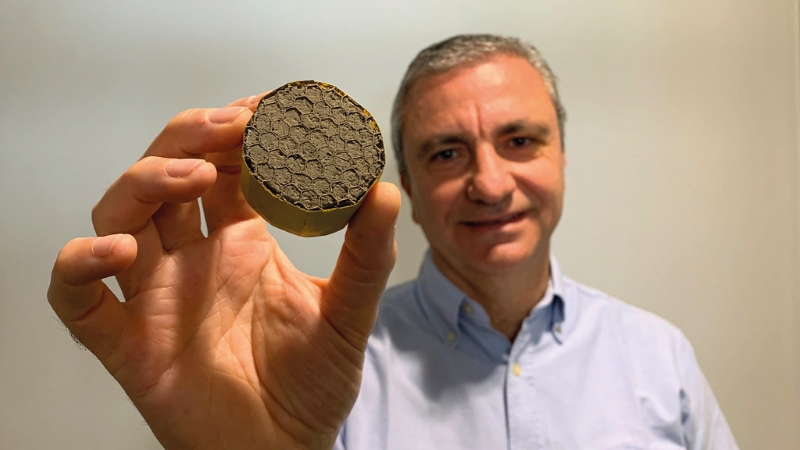

Michele Meo (MM) is a Professor of Smart Materials and Structures at the University of Southampton, UK

While still working as a full-time academic, he is also one of three directors and a shareholder of the University of Bath spin-out company Aerogel Core Ltd, which will develop next-generation thermal insulation and acoustic materials for the aerospace and automotive industries.

Jason Hallett (JH) is a Professor in Sustainable Chemical Technology at Imperial College London, UK

and has secured more than £10mln in research support, with several projects under commercial development. Nanomox develops advanced materials, such as metal oxide particles, with a reduced manufacturing impact.

How would you describe the difference between being an academic and running a company?

MM: Clearly, it’s a different world. Academia is more about doing research and sometimes this research doesn’t go anywhere. And then maybe 10 years later, somebody’s using your research. When you are running a company, it is more about what you are putting in and what you may get out. It is about cost, it is about profit, it is making revenue.

CE: I think the speed and the focus. When you have a company, you need to be clear on what markets you are addressing and what problem you are solving because you have limited resources – if you are in a competitive market, you need to understand what differentiates you from the competition.

JH: I am sure it depends on the company (and the academic?). At a very early stage in a deep-tech company they are quite similar. You are managing a small group of PhD-level researchers to try and figure out the answers to some key questions. It’s just that the questions are different. Later on, it diverges very rapidly – small companies have to be laser focused on their goals and their business plan. Academics can always find new and interesting problems to solve. Businesses have to resist that temptation or they will go nowhere…slowly. The other big difference is in who you deal with. Academics always care most about the technology, but most business leaders and investors do not. This was quite an eye-opening experience for me – I assumed the technology would be scrutinised more than the business plan. I was very wrong.

Did you find the transition to the commercial world tricky?

MM: Yes, especially negotiating with the University [his former employer the University of Bath] has taken a very long time. The company was formed by the University in April 2022, and we (Meo and his other researchers) became shareholders in January 2023.

CE: After my PhD I worked for a research centre, and I found whatever skills I had were transferable to a different context. You are learning every day and you need to make sure you are surrounding yourself with people that have been there and done it. Having the right network is important, but also skills in managing people, clients and finance are all transferable.

This is a learning journey and you need to make sure that you are identifying the gaps, and support that with either the right training or people. For people coming directly from academia, I don’t know how much of that they will have. It may be a little bit more of a transition, and this is why, in my opinion, a lot of people from academia stick with the CTO role rather than with the CEO role.

JH: Not really. I was working with colleagues that I knew well, so we kind of grew into it together. The part that is tricky is turning off the academic’s obsession with scientific detail – you really do have to move much more quickly in business than in research. The pace was the hardest adjustment for me. Of course, I only ever run the companies at an early stage – I’m too easily distracted by the research ideas.

What skills and attributes do you think are important to run a company?

MM: Academia is very similar in terms of management – managing people and managing time. And I guess it’s the same as a mini company. The company, however, has a lot of unanticipated tasks, such as nanoparticle safety, securing an office – which our team is doing in May, transportation, purchasing the goods. All things that people don’t anticipate.

CE: I think people management is very important. Having a strategic view because you are leading the whole thing. It’s not only about the technology, but also the people and the markets. Have a commercial-focused approach. A common mistake that companies may fall into is where they just focus on perfecting the product but the customer wants something much simpler and less sophisticated – that’s a disconnect between what the market really needs and what you are developing.

JH: Courage and decisiveness. They go together – you have to make a lot of decisions, often without very good information, and you absolutely cannot be afraid to make a mistake. You also need to be humble enough to admit those mistakes and pragmatic enough to then try and fix them. Academics always want to understand things completely, but there is never time in a company to gather enough information to really understand anything. Things move far too quickly.

How did you go about acquiring those skills – did you learn from other business leaders for example?

MM: We’ve been lucky to go through this process with ICURe [the pre-accelerator programme for researchers from Innovate UK]. It is a very good scheme for helping academics thinking about commercialising their research. The Research Fellow in our project went through a lot of training, such as market research and making a business case.

CE: Being in a start-up is a learning journey every day, I think people should not shy away from having a lack of skills here and there because you should have people to help, you should not be the one who knows everything. As part of the journey, I think learning is very important, and that would be supported by reading, attending webinars or training.

Most importantly is to have a network to support you, so people with similar journeys can help you. And as you go, as the company grows, you need to make sure that you are clear on what you don’t have. In a start-up, at the beginning, the CEO or CFO wears many hats. But, as the company grows, you need to make sure that you are clear on the skill gaps, and you are bringing in the people that will help close the gap. As a founder or a CEO, you don’t have a solution for everything.

JH: Absolutely. Mentors are important – people who can steer you onto the right path and make sure you stay on it. Finding those people can be easy, but you need to have a good level of trust that they know what they are saying. It is not as easy as gathering data to examine a hypothesis…and you really cannot afford to run business experiments to figure things out. You have to test and reject ideas quickly.

What would you recommend to academics and researchers hoping to commercialise their research?

MM: One thing that is important is always teamwork. Sometimes there are different views on how to create a product or tool or technology and so on. And what’s important is to focus because sometimes you think that you have an idea, which is important, but then you do the market research, and you see that the idea is not as important as you think. Having somebody who is telling you, “Look, don’t waste time on this, because nobody will ever be interested in this”, will help you stay on topic.

CE: For me, go out there and meet your customers as early as you can. Look for potential customers – what do they look like, how do they think, how do they see the solution. It is a tough journey. Make sure you are in it for the right reason. And make sure you are surrounded by the right people to support you, with their experience and skills.

JH: There is really only one question you need to answer – how will you make money? Pay attention to the market fit – if you cannot establish who will pay you, you have no business model. A great research idea (or even a great technology) does not necessarily make a good business. My best research ideas are not the ones that were commercialised. Great research is novel and disruptive. In some sectors (software and retail, for example) that can be an asset. In others (chemical manufacturing) it is a huge drawback. Don’t be too married to your ideas – you will find better ones.

What other learnings or insights do you think are worth sharing?

CE: You hear a lot of stories, such as people starting their company who exit in two years – that’s not the normal thing,

it is exceptional and depends on the sector.

It is going to be long and full of ups and downs. Make sure you are doing it for the right reasons – being there for the journey and enjoying it. Surround yourself with the right people, talk to your customers as early as you can. Make sure you build a strong team as well. You have to have a team if you’re a CEO, you have to build that team. There are three elements really – the product, the team, and the market. Sometimes if you are coming from academia, people focus more on the product or technology and forget the other two. They all go hand in hand.

Don’t get impatient by thinking I’m going to do this in two years, and get the money and go, because things happen. We had a pandemic in the middle of the first two years of the company. It was a tough time. We followed the strategy of survive, revive, thrive.

JH: One of my extremely brilliant PhD students founded a very successful and extremely impactful company based on no research, no intellectual property and no expertise. She discovered a problem and figured out a way to make money from solving it. She is an engineer who founded a company with a highly innovative business model – all the technology is off-the-shelf. My advice to budding entrepreneurs is always to pay close attention to this example – rather than try and find a problem your technology can solve (that rarely works), instead, try and find a problem you can solve.