‘Heat and beat’ 3D-printed steel

A new recipe for 3D laser-based printing allows greater control over a metal’s internal structure and can produce steel with tuneable strength and toughness, according to an international group of scientists.

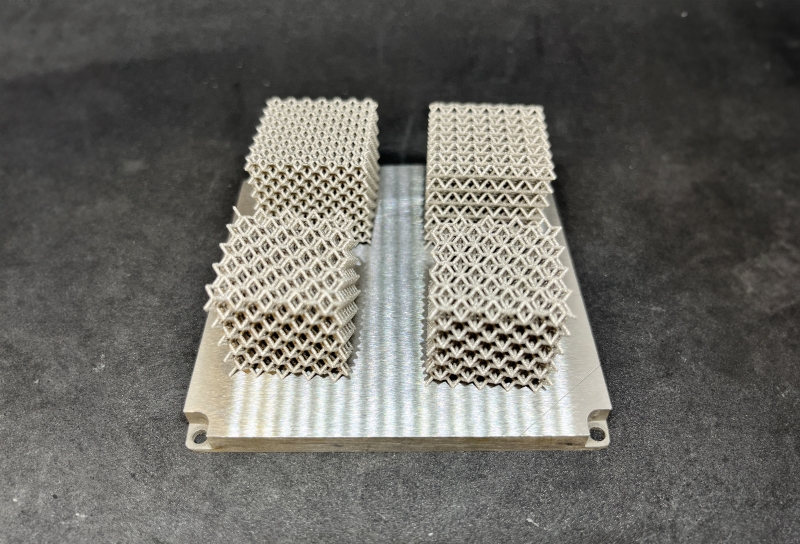

Example of stainless steel 316L lattice structures produced by laser powder bed fusion using the custom-made AddME Printer at NTU in Singapore.

© Dr Shubo GaoThe approach, developed by researchers at the University of Cambridge, UK, and assisted by colleagues in Australia, Finland, Singapore and Switzerland, combines the complex shapes that 3D printing makes possible, with the ability to engineer the structure and properties of metals without the traditional ‘heating and beating’ processes.

According to research lead, Dr Matteo Seita from Cambridge, the inspiration came from a 2020 study. 'Using transmission electron microscopy, we figured out that samples 3D printed using different laser parameters respond differently to heat treatment, and that these differences are linked to how uniform the material’s composition is at the microscopic scale.

'The less ‘mixed’ the alloying elements are in the material, the more resistant the metal becomes to the heat treatment.'

This prompted the team to consider using different laser-scanning strategies to tailor the thermal stability of stainless steel 316L alloy to control its recrystallisation propensity and its mechanical properties.

'The main challenge that remained was that we couldn’t use mechanical deformation during 3D printing to achieve that,' Seita explains. 'An alloy with low thermal stability still requires some mechanical deformation to undergo recrystallisation.'

Two strategies, which Seita describes as ‘surrogate heating’ and ‘surrogate beating’, are deployed.

‘Surrogate heating’ lowers the stainless steel’s thermal stability and involves scanning the laser beam over the material twice.

The first scan melts and consolidates the metal powders and also creates the target geometry, while the second scan homogenises the material’s composition and ‘mixes together’ the alloy elements.

The ‘surrogate beating’ involves scanning the laser beam back and forth across the powder layer following a fine pattern of lines that are very close to one another.

Seita notes that, compared to when a coarser pattern is used, the stainless steel undergoes more heating and cooling cycles, which, consequently, induce further material expansion and contraction.

Although the volume that expands and contracts is small and comparable to the laser spot size, each one of these events deforms the material by a small amount. He adds, 'It’s almost like using a microscopic hammer that deforms the material.'

Through the use of a fine laser-scanning pattern, the team asserts that enough events occur to induce the required cumulative deformation to trigger recrystallisation.

'By alternating these two laser-scanning strategies, we can then produce steel with low thermal stability and enough mechanical deformation to recrystallise, or steel with high thermal stability and low mechanical deformation to resist the heat treatment,' Seita says.

Computer simulations were used to estimate the material’s mechanical deformation during the heating and cooling cycles, and then these predictions were compared against real microstructure data from 3D-printed samples.

'We had to guess the thermal history in our large-scale samples from dedicated experiments at the synchrotron on small-scale samples, and then used this information to model microstructure homogenisation,' he explains.

Seita asserts that 'being able to control recrystallisation during 3D printing brings us one step closer to restoring the microstructure control capabilities that are used in traditional manufacturing processes, which could help foster industry adoption of 3D printing'.

More importantly, he says, 'these surrogate strategies could be used to make non-conventional, advanced alloys with complex microstructures that cannot be produced by any other manufacturing process'.