Flexible catheter to steer into the brain

Imperial College London, UK, scientists report that they are the first to have placed a bioinspired steerable catheter into an animal’s brain.

The early-stage research has tested the delivery and safety of the implantable catheter for diagnosing and treating brain diseases in two sheep.

The researchers believe the platform could simplify and reduce the risks of dealing with disease in the deep and delicate recesses of the brain. Accordingly, surgeons could see deeper into the brain and deliver treatment like drugs and laser ablation more precisely to tumours, as well as deploy electrodes more effectively for deep brain stimulation for conditions such as Parkinson’s and epilepsy.

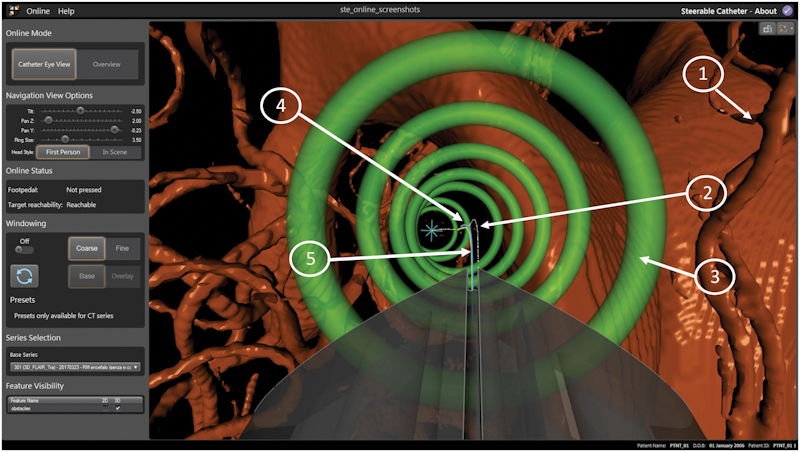

The soft and flexible catheter has four interlocking segments that slide over one another made of nanocoated, medical grade, implantable PVC. It is linked to an

artificial-intelligence-enabled robotic arm that fuses human input and machine learning to carefully steer the catheter into place. Surgeons then deliver optical fibres via the catheter, so they can see and navigate the tip via joystick control.

The catheter design was inspired by organs used by parasitic wasps that stealthily lay eggs in tree bark. In 2007, a biomimetics professor at Bath University delivered a keynote speech about the biological design. 'This inspired my young (and naive) mind to explore this wacky idea,' says senior author Professor Ferdinando Rodriguez y Baena.

Rodriguez y Baena made each of the four parts different colours to make surgical workflow safer.

Compared to traditional open surgery techniques, the team at Imperial proposes the device could reduce tissue damage during surgery, patient recovery times and post-operative hospital stays. They also note that the catheters that are currently used are rigid and difficult to precisely place.

The new catheter is designed for up to 28 days implantation with plans to extend this.

Rodriguez y Baena continues, 'We investigated drug delivery in full, with a selected lumen being used to insert a fused silica inner catheter for convection enhance delivery of a solution.'

To test their platform, the researchers have deployed the catheter into two live sheep at the University of Milan’s Veterinary Medicine Campus, Italy. The sheep received pain relief and were monitored for 24 hours a day over a week for signs of pain or distress before being euthanised for examination of the structural impact on brain tissue. The team found no signs of suffering, damage, or infection.

Rodriguez y Baena acknowledges that while sheep’s brains are similar in terms of composition to a human brain, they are many times smaller and so complex steerability is still to be fully evaluated.

Since publication, the working group has halved the size of the latest in vivo system and produced a 1.2mm catheter (outer diameter), but need to improve the radius further for tight bends and test the materials more before implantation.