Building a movement in straw-bale construction

Co-founder of the School of Natural Building, UK, Barbara Jones is passionate about building with straw and other natural materials.

'This is not something you can do' is a phrase Barbara Jones has heard repeatedly throughout her career. Made to feel that women could not be builders when she was younger, she never imagined the possibility. She was told that women are not strong enough for a roofing job, that builders can’t design and that you can’t build with straw. Good job she ignored all the naysayers.

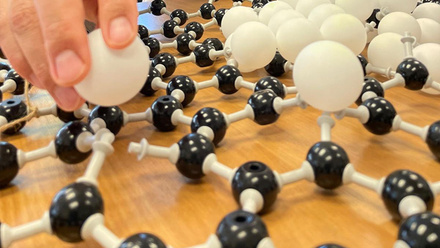

A passionate advocate of building with natural materials, she has been a leading exponent of straw-bale construction since the mid-1990s – designing affordable, straw-bale council houses; the largest load-bearing straw building in the UK; and has designed, built, or trained constructors to work on more than 300 other projects using the material.

The School of Natural Building (SNaB) she co-founded supports and trains a community of aspiring natural builders through theoretical and practical courses.

SnaB is signatory of the Alliance for Sustainable Building Products’ Anti-Greenwash Charter and firmly believes that straw 'pushes the boundaries of sustainability within the built environment”. Its related Straw Works website extolls how “straw is the perfect material to work with as it is, in itself, a waste product, it sequesters carbon and can be composted at the end of a building’s life. By using natural materials in this way, the construction of our homes can be regenerative and build resilience in the face of the climate emergency'.

The School was part of a European project called UpStraw, which produced the UK’s first Environmental Product Declaration for straw in 2021 and the nation’s first technical guide on straw-bale construction.

Jones and her team also advocate the benefits of using straw, alongside natural plasters lime and clay, for health and wellbeing – and the importance of designing buildings for health from the outset. These benefits include humidity regulation, prevention of bacterial growth and moulds, no toxic off-gassing, passive and active ventilation with breathable wall systems, and thermal storage for temperature control.

But the commitment to natural materials does not stop there. A trained carpenter and joiner, Jones can also work with wood and even pioneered the use of earth-filled car tyres for building foundations.

Finding her calling

At school, Jones wasn’t allowed to do carpentry or metal work because she was a girl.

Her first job was in fact in childcare in Barnet, London, after moving from West Yorkshire in the 1970s. It was only after chatting to the deputy head of the children’s home, whose father was a master carpenter, did Jones contemplate evening woodwork classes.

The classes taught students how to make kitchens, but as the only woman, the male teacher 'didn’t know what to do with me and he didn’t teach me very much'. It was awkward and off-putting, she recalls, and she assumed she wasn’t any good. It took her a bit of time to do the things she had been dreaming about.

Instead, with cuts to social care, including children’s services, Jones was realising the battle to instigate change was hard-fought. So, after a year she moved into drugs crisis in the voluntary sector.

At this time, she was squatting in a Hackney council house that had no gas, electricity or inside bathroom, and only cold water to the outside toilet. To try and improve her living situation, she sought advice from a retired neighbour and a nearby women’s electrical collective.

When Lambeth Council set up a Women’s Workshop, taught by established female carpenters, Jones promptly signed up. 'That was the turning point for me…It was a revelation, an absolute game-changer. It made all the difference in the world.'

She found the course empowering and discovered she was actually good at carpentry after all, which is why she believes women-only courses are 'absolutely essential' to help women work in construction.

After, Jones secured a place on a six-month-long intensive course at the skills centre alongside 300 men and one other woman. She found the carpentry and joinery course tough and intimidating, but it also came with an exemption from the first year of the City & Guilds professional course. It was then she realised she could be a carpenter.

She was initially self-employed for a spell before working with a mixed building collective, which employed about six people with very different skills, including one or two women.

They worked on short-life housing for housing associations. As well as carpentry and joinery, Jones assisted as a labourer, digging trenches for drainage or helping the electricians. This helped her garner on-the-job knowledge, and she loved it.

Jones says that 'it felt very positive and that things were changing for the better'. Many men in the building collectives were sharing their skills with women to help them work in construction.

But Jones still found sexual politics an issue, so she set up the first all-female building collective in the UK, called Hilda’s Builders. At their first job, renovating the ground floor of a big Victorian house into a self-contained flat in Clapham, London, Jones keenly felt the inherent contradiction at play – she couldn’t imagine earning enough for a mortgage to buy her own place. She realised she was only going to secure a roof over her head by building or renovating a home herself.

Nailing it

Hankering for fresher air and rural surroundings after seven years in London, Jones purchased two derelict houses with her partner in Todmorden, West Yorkshire, near to where she grew up.

She was able to work on the houses full-time for four years, having completed her second year of the City & Guilds course at Hackney College alongside her day job. Her partner was also a carpenter, joiner and builder, and had previously renovated a house.

After the project, her partner moved onto furniture restoration and bigger renovation projects. Meanwhile, Jones started Amazon Nails in 1989, a women’s roofing and building collective of up to 10 women.

One of their jobs included building an extension for Lambeth Women’s Aid back in London, which wanted female builders for security. But opponents claimed that 'women can’t do the job and aren’t strong enough', she recalls.

The tender for the job was a tiny paragraph in the Evening Standard newspaper, which Jones only saw as women at the refuge sent it to female builders around the country. Four-or-five different teams of women were involved, with Amazon Nails completing the roof carpentry and covering.

The care and attention from her team paid off, but it was hard-earned. 'If you’re a woman in this trade, men are going to really pick on anything you do that’s not right. And so you have to be 100% better than all of them.'

She says this is a common problem for women working in a non-traditional area. 'I had to be exceptional…You have to be outstanding, otherwise you can’t survive in that atmosphere.'

Green shoots

With the shoots of a green movement in the mid-1990s, Jones wanted to learn more about sustainable building methods.

Travelling for a year, she found jobs through a women’s network in the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, grafting for accommodation and food instead of cash.

At the time, her partner’s sister was a California-based artist who was building a straw-bale studio. Eight women took only two days to build the whole studio. 'Honestly, it changed my life completely doing that. I just thought, ‘wow, I cannot believe how simple and effective this is’. And from that moment, I knew this was my path. This is what I had to do.'

Returning to the UK, Jones secured a travelling fellowship back to California with the then Winston Churchill Memorial Trust.

Hooked on the simplicity, affordability and functionality, Jones hoovered up everything she could learn about straw-bale buildings in that time. 'I’ve always thought everyone should have access to good-quality housing, not just rich people. And so affordable housing for all has always been the thing I’m trying to achieve one way or the other.'

Jones explains how building with straw-bales started with the invention of balers in the late 19th Century, with a fallow period from around 1940 to 1980, before being revived in the US. During this period, straw-bale houses built in the previous century were rediscovered, with even residents not realising they were made from straw.

Jones discovered that around 350 bales of straw are needed to construct a three-bedroom, two-storey house. While any bale can be used to build, ‘construction-grade bales’ are dense, dry and uniform, and easier to use.

The Winston Churchill Trust secured her a slot on BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour so Jones could disseminate her new-found knowledge.

After only a four-minute appearance, Jones had to employ someone to field the large number of calls she received. She wrote an eight-page pamphlet on the topic to meet the demand for more information.

A farmer and magistrate in North Yorkshire was among those who got in touch, wanting to build a school to teach sustainable practices.

Jones quickly learned that keeping a client offsite is impossible when working with straw, because they are so keen to be hands-on. So, her team adapted to work alongside them, teaching them techniques quickly and supervising the quality.

But it was as frustrating as it was satisfying, as while the building was based on her ideas and design, she received no credit when the architect submitted the drawings for planning and building regulations. She has been doing her own drawings for the last 10 years and reports to have been underestimated by architects more than once. 'They say out loud, ‘you’re just a builder’.'

Her team returned to the site in the early 2000s to build the school dormitory, which Jones believes was the first building to use stone-rammed, car-tyre foundations. She got the idea from ‘earth ships’ she saw when travelling. These structures use tyres for the outside walls, which are built against an earth bank, with a south-facing glass wall.

Do as the Romans did

Not earning enough money through straw buildings, Jones did roofing jobs during the winter. Being limited to six-or-so projects a year, Jones changed Amazon Nails to a training company to cast the net wider. Initially, she taught 25 people at a time because of the swell in interest, allowing them to build a ground floor in just five days.

Jones was also pushing other natural building methods. In 1998, she became a Scholar with the Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust, who funded her to learn about lime and clay, which she still uses.

As well as a straw finish, Jones says lime could replace cement. She uses Limecrete for flooring like the Romans and highlights the misunderstandings about cement and concrete.

She notes that the lime the Romans and Greeks used is 2,000 years old and still going, while Portland cement was patented by John Aspidin in 1824, who died in Jones’ hometown of Wakefield. “Nobody used it before then, not even the Romans.” Modern-day cement was heavily used for civilian construction after the Second World War, having been deployed effectively by the military for infrastructure like runways, bunkers and airport buildings.

As the construction industry was decimated by the war, Jones says this broke the information chain across the generations. 'I feel very passionate about it because there’s so much misinformation and propaganda put out.'

Lime and clay display hygroscopicity, which is different to vapour permeability, Jones explains. Natural plasters and fibres can retain bound water in a non-liquid form, so can absorb moisture from a relatively high-humidity atmosphere without getting wet. 'That’s the crucial point which absolutely makes the difference between material quality and behaviour. It means that you don’t get condensation, damp and mould on houses with lime and clay plasters, and straw or other natural fibres.'

Also, in a straw building, the roof’s weight compresses the material, which is how load-bearing buildings used to be built, Jones says. The straw-bale compression varies depending on the density, but ‘construction-grade bales’ should depress less than 10mm. The best house design is simple, says Jones, such as a square or rectangle, so the roof weight can be spread evenly through the walls.

Building expertise

Amazon Nails became a social enterprise in 2007. It promoted straw buildings and engaged with community groups and self-builders, and also secured local authority contracts for council houses.

After Jones started designing with a Czech architect, they set up the company Straw Works in 2011 to focus on architectural design, while still providing training and construction services.

Straw Works designed and helped build the first Living Building Challenge structure. These are designed to be regenerative buildings that connect occupants to light, air, food, nature and community. They are meant to be self-sufficient and remain within the resource limits of their site.

Since choosing natural materials, 'I have been very principled about having every single last bit of the buildings being made of natural materials', Jones asserts.

She thinks the UK has been slower than many at building on expertise. 'We were the leaders in straw-bale building at the end of the ‘90s and we’re now at least 10 years behind France, if not more than other countries.'

She believes the UK construction industry needs to change track. 'People are not getting on board with the health benefits that you get with natural materials. There are no VOCs and no toxins with straw, timber, clay and lime – none. And our human biological bodies are in harmony with these materials and have always been.'

Highlighting the problems with chemicals in carpets, furnishings, cleaning products and paint, Jones believes that returning to using products with no toxic gases would make us all healthier.

Any resistance she faces hasn’t dampened her enthusiasm. 'I think I’ve got the best job in the world. I love what I do, and it has been challenging, but I’ve found ways around it.'

Jones is now a Technical Consultant on a straw panel project. She describes the EcoCocon panels developed as a game-changer, with the walls of a three-bedroom, two-storey house being erected in three or four days, while remaining affordable. While the panels are thinner, the clay plaster and external wood-fibre board – with a lime or timber cladding –result in a similar thickness.

These panels are millimetre accurate, she says, and comparable to any other structural insulated panels. Currently made in Lithuania and Slovakia, the team wants a UK factory in the next five years. The panels are CE marked and PassivHaus certified too.

The panels are also being used to build a 12-storey-high block of flats in Sweden – the Hyllie project. The UK only regulates straw buildings to below 18m, because the industry doesn’t understand how timber and straw behave in a fire, notes Jones.

Straw bales can be more fire resistant than most modern materials, Jones asserts. While straw can be a real fire-risk in a certain form, dense straw has only enough air to be a good insulant, not enough to combust, she explains. It acts similarly to large-dimension timber, charring outside protecting the inside.

Jones thinks there are embedded hurdles in UK construction law, with no way to argue. She has pushed her innovations by finding individuals who 'recognise common sense'. But, if an engineer cannot accept her arguments, she moves on to the next idea. Despite many heated discussions with building inspectors and engineers, Jones sees a change.

'It doesn’t make me a millionaire, but I don’t care because I want this to happen. This needs to be out there. This is the best idea that there is.'