A minerals makeover?

The Critical Minerals Association’s annual conference focused on ‘Breaking new ground’ in supply.

Dr Shobhan Dhir, Critical Minerals Analyst at the International Energy Agency (IEA), gave a useful overview of the ups and downs in critical minerals supply chains in recent years, giving context to the Critical Minerals Association's (CMA UK) conference, ‘Breaking new ground’, last December.

He noted how greater focus on, and demand for, critical minerals emerged in 2021, with prices, particularly for battery metals, spiking in 2021-22. Lithium prices skyrocketed eight-fold in just two years. But 'why did prices fall so dramatically over the last year, losing all those gains?' Dhir noted supply came online quicker than expected from emerging areas in Africa and Indonesia.

The IEA says investment in non-ferrous metal mining grew 10% in 2023, and investment in lithium mining increased 60%. Exploration spending also rose 15% that year, led by Canada and Australia.

At around US$325bln, the agency estimates today’s aggregate market value of key energy transition minerals to align broadly with the market for iron ore. Dhir reported solar capacity to have doubled in 2023 and battery storage capacity more than doubled, having already doubled in 2022.

The IEA forecasts the combined market value of key energy transition minerals to more than double to US$770bln by 2040 in a net-zero emissions scenario, but anticipates challenges in securing enough critical minerals to meet this target by 2050.

Dhir noted copper and lithium to have particularly major supply deficits by 2035, based on announced pledges in the base-case scenario. Copper is predicted to meet 70% of expected demand, yet ore quality is declining. Announced lithium projects only meet 50% of the predicted demand by 2035, although there are growth areas like Argentina and Zimbabwe.

A base-case 2035 scenario forecasts cobalt supply to meet 85% of demand. Graphite and rare-earths are also seen as well supplied, but the key challenge is market concentration. The supply chain for critical minerals is limited as refining is dominated by a few countries, especially China.

UK's vulnerability

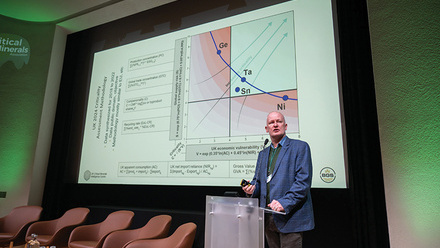

Against this backdrop, Gavin Mudd, Director of the UK’s Critical Minerals Intelligence Centre, briefed the audience on its latest Criticality Assessment.

Out of 82 materials assessed, 34 minerals are deemed ‘critical’. This is an increase from a 2021 assessment where 18 minerals out of 26 were designated as such.

Notable additions are nickel, iron, germanium, aluminium and chromium. Copper is still not included, along with many other metals that are below the threshold, but are on a watchlist. Palladium has moved from being on the list to below the criticality threshold.

The new list reflects the increased scope of assessment and advances in the methodology used. Mudd highlighted the importance of thinking about other securities not just the energy assessment.

Several issues are at the heart of this – namely technology-driven mineral demand, materials that can withstand harsh environments and artificial intelligence. Trade regulations also have a significant impact. And while recycling may be able to sustain some supply chains, this varies depending on the type of mineral. The review focused on the last five years of data.

Partnering up

Oliver Richards, Head of Critical Minerals and Mining at the Department of Business and Trade, highlighted the UK’s new Invest 2035 strategy and recent target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels by 81% by 2035. Both rely on critical minerals. The government therefore wants to see domestic projects grow, backed by the National Wealth Fund (NWF) and academic research.

While internationally, nine agreements have been signed with partners on a bi-lateral basis, including Indonesia a few months ago.

Multilaterally, the UK is engaged in different forums, including the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP). The core group consists of 15 different member nations that want to drive investment into sustainable critical mineral value chains. The MSP Forum consists of 15 producer countries that work with these partners.

UK Export Finance (UKEF) became a founding member of the MSP Finance Network in September 2024 to focus capital on meeting this demand for minerals. Pensana and HyProMag are two UK companies spun-out from academia that work in the rare-earths sector and have benefitted from the MSP.

The UK Government’s Critical Minerals Strategy, due to be launched this year, will further focus on boosting international collaboration to bolster national supply chains and security, while delivering new jobs and economic growth.

In that regard, at the time of going to press, 16 British critical minerals companies joined a trade mission to Saudi Arabia to boost collaboration in securing minerals supplies.

George Hames, Regional Head of UKEF, explained how allocated funding from the last Autumn Budget could provide capital for overseas projects that source critical minerals for use in UK industries.

This could help the UK build economic resilience and lower the risk of supply-chain disruption in major industries.

Credit guarantees to overseas companies will help them access debt financing for projects that supply UK exporters with critical mineral products – including both raw and processed materials.

This would make it easier for UK manufacturers to secure contracts with critical mineral suppliers in countries with large mineral deposits.

The UKEF can grant up to 100% of financing to a maximum of twice the offtake contract.

A European perspective

Ludivine Wouters, an advisor to mining companies and investors at Latitude Five, offered a broader European perspective.

One shift in approach is the growing defence agenda, with the first EU Defence Commissioner.

The second shift is the rise in competitiveness. '[Critical minerals have] gone from being an element of the EU Green Deal…to…a realisation that there are immediate and existential threats to EU global positioning…EU ambitions and strategies.'

Wouters said getting 27 nations to agree to a whole economy approach is almost impossible, but the new EU Commissioner for a just and competitive transition is drawing up an industrial deal. 'The UK, to put it bluntly, is back on the agenda because of its role in that integrated strategy.'

Margery Ryan from Johnson Matthey praised the UK’s ability to recycle 60% of its platinum group metals. She said it was important to use the nation’s materials science and metallurgy expertise, and leverage London’s position as a global finance centre. She pointed to fuel cells as a rare, but real, example of the UK and EU being competitive while China is catching up.

Phillippa Varis from Mkango Resources Ltd, with 30 years in the mining industry, also sees an opportunity for Europe to work together. She argued that multi-lateral partnerships give the region credibility with emerging economies and suppliers of critical raw materials, and echoed the UK’s position as a strategic hub for finance.

But investment in exploration, mining and minerals processing is key, emphasised Varis. Yet she noted that investor confidence is at an all-time low, with competition from both within mining and other sectors.

This is exacerbated by capital project overruns in the mining industry. While Varis points out that these have gone down from 60% to 53%, she says, 'We are saying [to investors] ‘give us money, we want to build this major project, but we are going to probably come in 50% over and our schedule is probably going to be 70% longer than we told you it is going to be’. These are very real challenges that are affecting confidence in our industry'.

The catch-22 she highlights is that the lack of sufficient financing products leads to these project overruns.

Jamie Strauss, Founder and CEO of ESG technology provider Digbee, also noted the challenge of 'execution risk' in encouraging 'new money'. With 80% of specialist money disappearing over the last 15 years, Strauss asks, 'What are we doing to encourage new money?' He thinks the sector needs to improve trust and confidence to give greater certainty.

Quoting McKinsey’s 2018 analysis, he outlined how around 85% of all development capitals have gone over budget and beyond time, and on average 45% are over budget.

Varis also pointed to the ongoing fluctuations in metal prices affecting investment, with the UK’s Transition Finance Market Review identifying long-term policy uncertainty and sector credibility as risks too. The latter has been damaged by greenwashing and delayed decarbonisation plans.

A number of high-profile issues with environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance has added to the sector’s problems. 'Whatever solutions are chosen need to address all of these issues to be successful in the marketplace,' asserted Varis.

Strauss insisted, 'Sustainability is just good business. Having a relationship with a First Nations group, for instance, is like a marriage. Once that is done, it becomes much easier. You get better employment, better power contracts, etc.'

He stressed that the market now needs the sector to communicate its responsible investment, which will lead to responsible production and responsible materials.

And there is scope for Europe to set the standards for performance, which plays to the UK’s strength.

Reflecting on her 10 years spent negotiating deals with African countries, Wouters is nervous about how this is approached, and Ryan also expressed concerns about the EU seeming to lecture other nations on standards rather than approaching these countries as equal partners and investing in the local community. Ryan feels it is all about the market the industry creates, which allows supply to do the right thing. She thinks there is space for the UK to create that market-led approach.

The World Gold Council’s work with Chinese companies to create a unified set of standards, as well as its work on artisanal mines, was highlighted by Varis as a positive example towards making a paradigm shift both locally and at a government level.

Risk and restructuring

Building on the discussion around investment challenges, Simon Gardner-Bond from TechMet, a private investor in critical mineral projects, explained that the biggest problem for long-period financing is the volatility of the commodity price. Financiers, especially on the debt side, therefore find investing unpalatable. The lithium prize, because of its short history, becomes 'almost impossible to finance,' he observed.

With TechMet co-investors in Cornish Lithium, Gardner-Bond emphasised patience for investors. He also argued that governments probably need to provide the investment for that longer-time period that makes equity investors uncomfortable. 'This is essentially the main reason why the Chinese have gained a 20-year head-start on us.'

Jeff Townsend from CMA (UK) added, 'In 2020, we were told the market has to work, and the reality is, it is a broken market and state intervention is now the new norm.'

Dr Sarah Gordon, Co-Founder & Global CEO of risk management and sustainability consultancy Satarla, also recalled conversations with members of government who said the market will sort it. She told them it would be too late. 'With climate change as the ticking clock…we need to move really fast…How do we inject that certainty into those investments and those business opportunities, and what is the role of policy taking away some of the risk we might face?

'Going back to 2020, when COP26 was hosted in Glasgow, mining was basically told ‘you are not welcome here’ because [it] has no role in the energy transition. Luckily, I think some people realise that was a slightly embarrassing stance to take. To give everybody involved credit, and especially the CMA (UK) for its work, we are now in a very different state.'

On the topic of state intervention, James Whiteside, Director at the NWF, says he often hears from UK projects that grant funding is better than in the past, but the ‘valley of death’ is with growth equity post-pilot stage. The NWF seeks to address that, with £28bln of capital now available. It sits between government and the market.

Its first preferred equity investment was in Cornish Lithium, along with TechMet, as they moved into the demonstration stage. More recently, the NWF has announced investment in the South Crofty tin mine, also in Cornwall.

The NWF has also made its first capital markets deal with a listed investment in Invinity Energy Systems – a vanadium flow battery company looking to build a factory in Motherwell. The Technology Readiness Level needs to be seven or above, matching capital or greater at a minimum of £25mln. 'We can take some of that early-stage risk,' Whiteside explains.

Tightening up the timelines from exploration to operation would definitely help, reflected Townsend and Gardner-Bond.

Strauss noted Norway, Canada and Australia are all accelerating responsible critical minerals extraction. The permit authorities having trust in the management teams to be responsible is key, and improving execution improves confidence, resulting in faster permitting.

Gardner-Bond pointed out those countries have better tax breaks for exploration and development, albeit like most of Europe.

You need hundreds of exploration projects out there, noted Gordon, to find the one successful mine. 'Which either means exploration companies are rubbish, or it means we are not necessarily collecting the right data…' Speaking as a geologist, she said that often all we care about is the rock and the commodity, which is why many projects fail. Having the most glorious deposit is irrelevant if you haven’t properly understood what is happening at the surface, so exploration may require new technology.

Evaluating different datasets will speed everything up. 'Putting more emphasis on the right data helps policymakers, investors, etc., jump on board with the right projects at the right time,' she extolled.

Gardner-Bond felt that governments always seem to want others to verify or reduce the risk, but after an engineering or feasibility study it is a lot easier to raise money from the private sector, and government backing is needed earlier.

Whiteside agreed that UK grant funding is quite good and is there to upscale companies to commercialisation, but growth capital is the real ‘valley of death’ in this country.

Gordon confirmed a good amount of investment into blue-sky thinking, but felt the UK to be poor at getting start-ups flourishing. 'We sell all our ideas to other countries. We are really bad at making our way through that.' She felt the responsibility to be with lots of different parties, not just government.

Elsewhere, Strauss cited Sweden’s Northvolt having financial difficulties and Portugal losing a lithium refinery. Governments have to step in, he urged, to reach these goals. 'We have got to change, transform and become nimble if the critical mineral goals are to be achieved.'

Opportunities there for the taking

'If you take an insurance approach to calculating risk you will never do anything new,' Gordon mused. 'As a risk management professional, risk is not just about trying to prevent loss, it is finding the upside and opportunities. It is taking charge of the uncertainty you might experience in the future.'

Flinching when ESG is mentioned negatively, Gordon stressed it is about unlocking resources in different parts of the world and turning a mine into a development project. Albeit a much longer timeframe, it is a much bigger sales pitch, she emphasised.

Gardner-Bond concurred that if you can’t do a project in a responsible, sustainable and well-supported way, you have to pause everything. That is why Cornish Lithium was easy to invest in, he noted. ESG shouldn’t be a drag on the project, just a part of it.

Strauss also emphasised that ESG is being cast in the light of negative bureaucracy and compliance – the mining sector is in the top quartile of ESG numbers yet has the worst valuations. So, there is a complete disconnect. 'This industry is behind the curve with the way we want to communicate it to our advantage, and so we are pulling the sector back relative to communities, finance, permitting and every other aspect of the lifecycle, and we have got to reverse this to a positive.'

All sectors are transforming, Strauss highlighted, citing the power industry, car sector and AI developments. How do we embrace this change and take risk, he asked.

'This sector produces so many good things, whether it be schools or hospitals, direct or indirect jobs, but we don’t communicate that in a way to take the opportunity from a 3.5x cashflow to a double-digit cashflow and be perceived by society in a really positive way.'